Inequality Fun and Their Applications

This article assumes the reader has basic knowledge of calculus and analysis. Covers topics ranging from basic Cauchy Schwarz to Lipschitz, culminating in us pulling out a mathematical rabbit out of an algebraic hat.

1. What is an Inequality?

An inequality compares two values, showing if one is less than, greater than, or simply not equal to another value. Literally, it does not get more simpler than that. For example: \(3 \leq 5\) directly reads “3 is less than or equal to 5.” Whereas \(14 \geq 2\) reads “14 is greater than or equal to 2.”

2. Inequalities in Calculus

Now, we cover some basic and interesting inequalities in calculus and discuss their implications in a bigger picture. We will be utlizing the concept of vectors and spaces.

2.1 Cauchy-Schwarz Inequality

One of the first (and most important) inequalities we cover is known as the Cauchy Schwarz Inequality. We first define two vectors \(u\) and \(v\) in \(\mathbb{R}^n\) given the following form:

$$ u = ( u_1, u_2, …, u_n) \quad v = ( v_1, v_2, …, v_n) $$ Given these two vectors, Cauchy Schwarz states that: $$|u \cdot v| \leq |u| |v|$$ And in coordinates, this is written as: $$ |u_1v_1 + u_2v_2 + … + u_nv_n| \leq \sqrt{u_1^2 + u_2^2 + … u_n^2}\sqrt{v_1^2 + v_2^2 + … v_n^2} $$ While this inequality has no significant real world applications, this inequality comes in particularly handy for many max/min problems with constraints as well as math olympiad questions. For example, if we know that \(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1\) and we want to find the maxmimum \(x + 2y + 3z\), we can utilize the inequality by finding different vectors that represent the over equation.

Take the vectors $$u = (1,2,3) \quad \text{and} \quad v = (x,y,z)$$

We can see that \(u\cdot v = x + 2y + 3z\) which is our original equation we want to maximize. We invoke Cauchy Schwarz and arrive at the inequality that: $$ \begin{align*} x + 2y + 3z &\leq \sqrt{x^2 + y^2 + z^2}\sqrt{1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2}\\ &\leq \sqrt{1}\sqrt{1^2 + 2^2 + 3^2} \\ x+2y + 3z &\leq \sqrt{14} \end{align*}$$ We see that the maximal value is obtained at: $$x = \frac{1}{\sqrt{14}}\quad y = \frac{2}{\sqrt{14}} \quad z = \frac{3}{\sqrt{14}}$$ which satisfies the constraint as well. One can also note that when plugging in generic variables, a general form of the equation can be found with the constraint \(x^2 + y^2 + z^2 = 1\) to maximum \(ax + by + cz\) where \(x,y,z\) are: $$x = \frac{a}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2 + c^2}}\quad y = \frac{b}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2 + c^2}} \quad z = \frac{c}{\sqrt{a^2 + b^2 + c^2}}$$ Now, we continue onto the triangle inequality; another fun application.

2.2 Triangle Inequality

The triangle inequality is also an extremely well known inequality in math. Geometrically, it states that the sum of the lengths two sides of the triangle cannot exceed the length of the largest side. Through the triangle inequality, one can find a reasonable range of distances and quantities something can be given knowns and unknowns. For example, given the unknown difference between two cities, one can use the triangle inequality to indirectly calculate the distances between two cities. For example, below, one can use the triangle inequality to get a rough estimate of the distance between two cities without knowing the true distance.

2.3 Chebyshev’s Inequality

Another fun inequality is also a pretty important tool for solving Math Olympiad similar problems. This is known as Chebyshev’s inequality. If we are given two monotone sequences (sequences constantly increasing and decreasing): \(\left\{x_i\right\}, \left\{y_i\right\}\) and the sequences are similarly ordered, then: $$n\sum^n_{i=1}x_iy_i \geq \sum^n_{i=1}x_i\sum^n_{i=1}y_i$$ If the two sequences are oppositely ordered, then we get the result of $$n\sum^n_{i=1}x_iy_i \leq \sum^n_{i=1}x_i\sum^n_{i=1}y_i$$ When both sequences are constants, then the sums are equal. To use this, we can explore a similar problem. Assume that \(a,b,c \in \mathbb{R}\), then we want to show the following result: $$\frac{ab}{a+b}+\frac{bc}{b+c}+\frac{ca}{c+a}\leq\frac{3(ab+bc+ca)}{2(a+b+c)}$$ We assume that \(a,b,c\) all belong to a monotonic sequence (i.e. \(a\geq b\geq c\)). Thus, we can use a form of Chebyshev’s Inequality. We note that: $$a +b \geq a + c \geq b+c$$ Because of the properties of fractions, we can also see that $$\frac{ab}{a+b}\geq \frac{ac}{a+c} \geq \frac{bc}{b+c}$$ Combining both sequences, we see that the desired quantity is acheived: $$\frac{ab}{a+b}+\frac{bc}{b+c}+\frac{ca}{c+a}\leq\frac{3(ab+bc+ca)}{2(a+b+c)}$$

2.4 All Things Means (and Inequalities)

One last type of inequality (more of a subsection that deserves its own article potentially later) tying together a few different means. We will only discuss a few main means, however, the methods of averaging a set are endless. Thus, we will only discuss the most basic properties and applications in means. Usually, most people are familiar with the following mean: add a number of items up, then divide by the number of items \(n\). In mathematical notation, that is described as: $$\text{Arithmatic Mean} = \frac{1}{n}\sum^nx_i = \frac{x_1+x_2+…+x_n}{n}$$ The applications of this usually arise in the case of data collection or basic statistics. Frequently, this comes in the form of describing results from a survey. One downfall of this is that it is not usualy a robust (or dynamic) statsitics: meaning it can be influenced greatly by the presence of outliers. Two more means are the geometric mean and the harmonic mean which will be discussed up next.

The geometric mean usually arises in cases of natural numbers and is calculated with their product (not their sum like arithmatic mean). Usually, the geometric mean is used in cases where the numbers one is dealing with is exponential in nature or are meant to be multiplied. Values like these are usually growth rates (human growth rate, banking rates). The geometric mean is defined as follows: $$\text{Geometric Mean}=\left(\prod_{i=1}^n x_i\right)^\frac{1}{n}=\sqrt[n]{x_1x_2x_3…x_n}$$

Finally, we look at the harmonic mean. This is (yet) another form of average that can be useful in certain contexts. In the case of numbers defined in relation to a unit or rates such as, speed, acceleration, force, etc., the harmonic average provides a better and more accurate estimate than the other two. The harmonic mean is defined as follows: $$\text{Harmonic Mean}=\frac{n}{\sum_{i=1}^n\frac{1}{x_i}} = \frac{n}{\frac{1}{x_1}+\frac{1}{x_2}+\frac{1}{x_3}+\frac{1}{x_n}}$$ Knowing these three means, we can define the following inequality: $$\text{Arithmatic Mean}\geq \text{Geometric Mean} \geq \text{Harmonic Mean}$$ When all of the samples are equal in count and measure, then we have equality. The proof of this is left as an exploration for the reader. Usually, this property has no real life application (as far as I know), and most of their applications tend to shine in doing math olympiad and Art Of Problem Solving-esque problems (AOPS).

3. Inequalities in Analysis

Moving past the world of calculus, one can start looking into the branch of mathematics known as ‘analysis’. On a high level, real analysis relates to studying the real number line and the reals (\(\mathbb{R}\)). There is also complex analysis which studies complex number plane (\(\mathbb{C}\)). We only look at applications of inequalities within analysis. In real analysis, most of the more-studied topics include sequences, series, functions, integration, and power series. Since we covered the triangle inequality in an earlier section, we revisit it now in the following to see its applications inside of analysis.

3.1 Triangle Inequality Applications

First, we redefine the triangle inequality as \(|x + y| \leq |x| + |y|\) i.e. the length of the largest side cannot exceed the sum of the lengths of the two smaller sides. Next, we visit a useful property inside of analysis known as the Archimedean property. The Archimedean property states that for any number \(x \in \mathbb{R}\), there exists a number \(n \in \mathbb{N}\) such that \(n>x\). Simply put that for any real number on the line, there always exists a natural number that is larger than it.

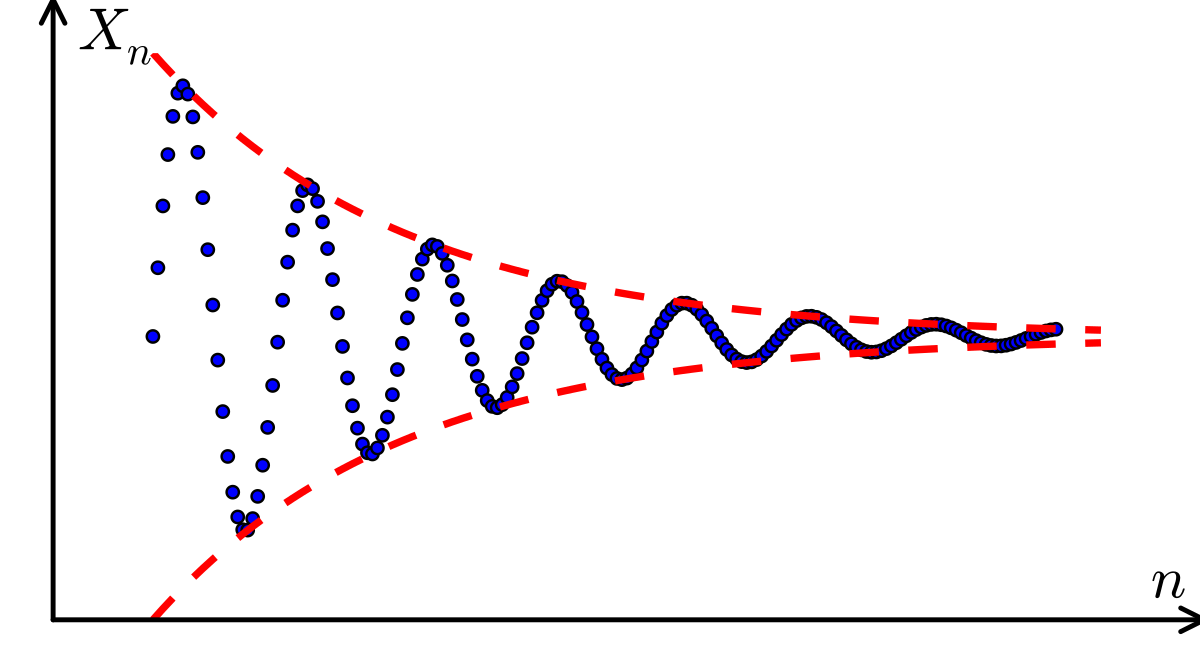

Another thing we define is the Cauchy sequence. A Cauchy sequence is a sequence of real numbers \(\{a_n\}\) such that for every \(\epsilon > 0\) there exists a positive integer \(N\) such that

$$|a_m - a_n|< \epsilon \quad \text{when}\quad m,n\geq N$$

Stripping away the mathematical jargon from there, a cauchy sequence is one where the farther we go along the sequence, the closer the points get to each other. Until there is an \(N\) index where all of the points past that grow an epsilon distance close to one another.

Now, knowing the definition of various terms and with our triangle inequality, equipped, we can take on a simple proof involving the previous tools. In this case, we want to show that a Cauchy sequence is bounded.

Now, knowing the definition of various terms and with our triangle inequality, equipped, we can take on a simple proof involving the previous tools. In this case, we want to show that a Cauchy sequence is bounded.

To do this, we first suppose \(\{a_n\}\) is a Cauchy sequence. We take \(\epsilon = 1\) means that there is some index \(N\) where \(|a_m - a_n|< 1 \;\forall\; m,n \geq N\). Thus, seeing this, we are able to split up our series into two pieces. One up to \(N\), and one from \(N\) onwards. We now see that the finite piece is also bounded by \(M\), with this in hand, combining the sequence and the triangle inequality, we see that: $$|a_n| = |a_n + a_N - a_N| \leq |a_n - a_N| + |a_N| < 1 + M$$ Thus, it obviously follows that the Cauchy sequence is bounded by \(1+M\), thus concluding our proof. This is an elegant way of seeing how we can use the triangle inequality to help us prove things. Now, this is merely a simple example of an application of such inequality. Moving deeper into analysis, the concept of a metric space is observed. A metric space \((X,d)\) is a set \(X\) and distance measure \(d(x,y)\;\forall\; x,y\in X\) on that set. Without diving in too deep and deviating from the original purpose of the article, one can use many types of inequalities within a metric space to help prove different results.

3.2 Lipschitz Functions

One more fun excursion into metric spaces and all things analysis, we cover the concept of a Lipschitz function. This is a strong form of continuity (uniform to be exact) for functions. For a function to be Lipschitz continuous, we invoke the following definition (and inequality). Given two metric spaces \((X,d)\) and \((Y,d)\) with corresponding distance metrics, a function \(f: X\rightarrow Y\)is Lipschitz continuous if the following is satisfied: $$d_Y(f(x_1), f(x_2))\leq Kd_X(x_1, x_2)$$ where \(K\) is known as the Lipschitz constant. In a simpler case of a function that maps the reals to the reals, a function \(f: \mathbb{R}\rightarrow\mathbb{R}\) is Lipschitz continuous if the following is satisfied: $$|f(x_1) - f(x_2)|\leq K|x_1 - x_2|$$ and \(K\) is the same Lipschitz constant. This proves to be much more powerful for us as Lipschitz implies continuity and a whole other slew of properties which can be helpful in many scenarios.

4. Conclusion

Throughout the article we see the power of many inequalities and their applications as well. From real life applications to alot more on the theoretical side, the inequality is something that is pervasive throughout every branch of mathematics. Approxamating a distance between two points? Use a series of triangle inequalities! Proving function continuity? See if it is Lipschitz first! The use cases are endless. For those who want to read on, here is a fun application of inequalities and the means discussed in the article.

4.1 A Mathematical Rabbit out of an Algebraic Hat

From Cut The Knot, the describe an interesting way to pull the mathematical rabbit out of a metaphorical hat in some sense (i.e. pulling a result from thin air). We want to prove a 3 term AM-GM inequality. We seek to prove that $$\sqrt[3]{abc} \leq \frac{a+b+c}{3}$$ We can see that: $$ \begin{align*} x^3 + y^3 + z^3 - 3xyz =\frac{1}{2}(x+y+z)((x-y)^2 + (y-z)^2 + (z-x)^2) \end{align*}$$ Plugging in \(a=x^3,\; b=y^3,\; c =z^3\), we get our desired result. It is up to the reader how we got the following equality :)